Plant of the Month - March 2019

Salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis)

Salmonberry is a medium to tall deciduous shrub closely related to garden raspberry. Its compound, three-parted leaves, its upright, prickly stems, and its aggregate, raspberry-like berries comprised of multiple one-seeded drupelets, all signal this relationship. But, salmonberry is its own plant with its own special features. Its 5-petalled flowers are bright pink, with pointed, spreading petals. The flowers often appear on the bushes in early spring before the leaves expand, signalling the start of the growing season all up and down the coast. The petals, which are somewhat pointed and spreading, are underlain with five greenish sepals. In the centre are multiple pollen-bearing stamens and numerous pistils, one for each druplet of the fruit. The flowers contain a sweet nectar that attracts hummingbirds, bees and other pollinators.

The berries start to ripen in May – among the earliest of the fruits – and can grow up to 2 cm long. Depending on the genetic makeup of the plant, the ripe berries range from golden yellow on some bushes, to bright ruby red, or to a deep, dark red on others. When fully ripe, salmonberry are juicy and flavourful, although they tend to be watery, and not as easily dried as some other berries. They are delicious eaten fresh, right from the bush! Picking berries of all the different colours together makes a beautiful collage. You can also make them into pies, jams and jellies, alone or mixed with other fruit.

This shrub is relatively common and spreads easily by underground stems or rhizomes, so that it forms dense thickets, especially in areas of rich, moist soil. New shoots sprout up from the ground in the springtime, then harden and become woody by the summer. The bark is yellowish brown and somewhat shredding. The prickles are found all along the stems and along the undersides of the leaves. Salmonberry is susceptible to drought, and grows best in damp clearings, along creeks and the edges of marshes, wet forests, and roadside ditches. It is common all along the West Coast of British Columbia, ranging into the interior along some of the river valleys.

As well as being related to garden and wild raspberries, salmonberry is a close relative to many other familiar berries, all in the genus Rubus, including thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), blackcap (Rubus leucodermis), and blackberries, both our native trailing blackberry (Rubus ursinus) and introduced Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus).

For Coastal First Peoples, salmonberry was, and still is, an important plant. Not only does it provide delicious berries in late spring and early summer, but even before the berries are ready, the tender, succulent young shoots can be broken off, peeled and eaten as a springtime green. Many Elders recall eating these greens, often accompanied with salmon eggs, oulachen grease (a rich oil rendered from a small smelt) and, in recent times, sugar. Children have enjoyed harvesting these shoots, which are commonly called “saski” (a rendering of the name for the shoots in several Coast Salish languages (e.g. Straits Salish and Hul’q’umi’num’,théʔthq’iand Squamish, stsáʔtsqay). The berries are called by various names in different languages. In Hul’q’umi’num’ (Halkomelem), the language spoken by the Stz’uminus and Snuneymuxw of the Yellow Point area, they are called lila’[“lee´-laa’”] or əlílə[“alee´-la”]. In many of the coastal languages, there are also separate names for the different colour forms of salmonberry. For example, in the Straits Salish language, spoken on the Saanich Peninsula and Victoria area, there are names for very light-coloured berries (pəlpəq’xəlíqw‘white ones’), the dark ones (nəq’íx ‘black’), the golden ones (nənəl’pxwíqwOR nəlpxwíqw ‘blond’), and the bright red ones (nənəl’kwəmíqw‘red’).

Swainson’s Thrush, called called xwəxwə́ləsh [xwexwelesh] in Straits Salish,is widely known up and down the coast as the “Salmonberry Bird”. It is said that the singing of the Salmonberry Bird makes the berries ripen.The song, in rising flute-like tones, if translated, names the different colours of salmonberries and encourages them all to ripen: The little bird is singing, “nenel’q'xelíqw ['little black/dark red-headed ones']! nenel’pq’íqw ['little white-headed ones']!nenel’kwemíqw ['little red-headed ones']!nenel’pxwíqw ['little blond/golden-headed ones']!xwexwelexwelexwelexwesh![‘ripen, ripen, ripen, ripen!’].”

Saanich elders Violet Williams and Elsie Claxton told a story about xwexwelesh and Raven, as recorded in Saanich Ethnobotany:

Swainson's Thrush invited Raven to her house for a meal. She told her kids to take their baskets out to pick berries. She started singing her song. In her song, she nicknames each of four colours of salmonberries and then sings their common names. As she sang, her children's baskets filled up. Afterwards, Raven said, "You come to my house." Swainson's Thrush did. Raven told his children to go out with their baskets. They did that for their dad. Raven sang and sang in his croaking voice, but the baskets never got full.

This story teaches us that singing to ripen the salmonberries is a talent only of the Swainson’s Thrush, and Raven does not have this ability.

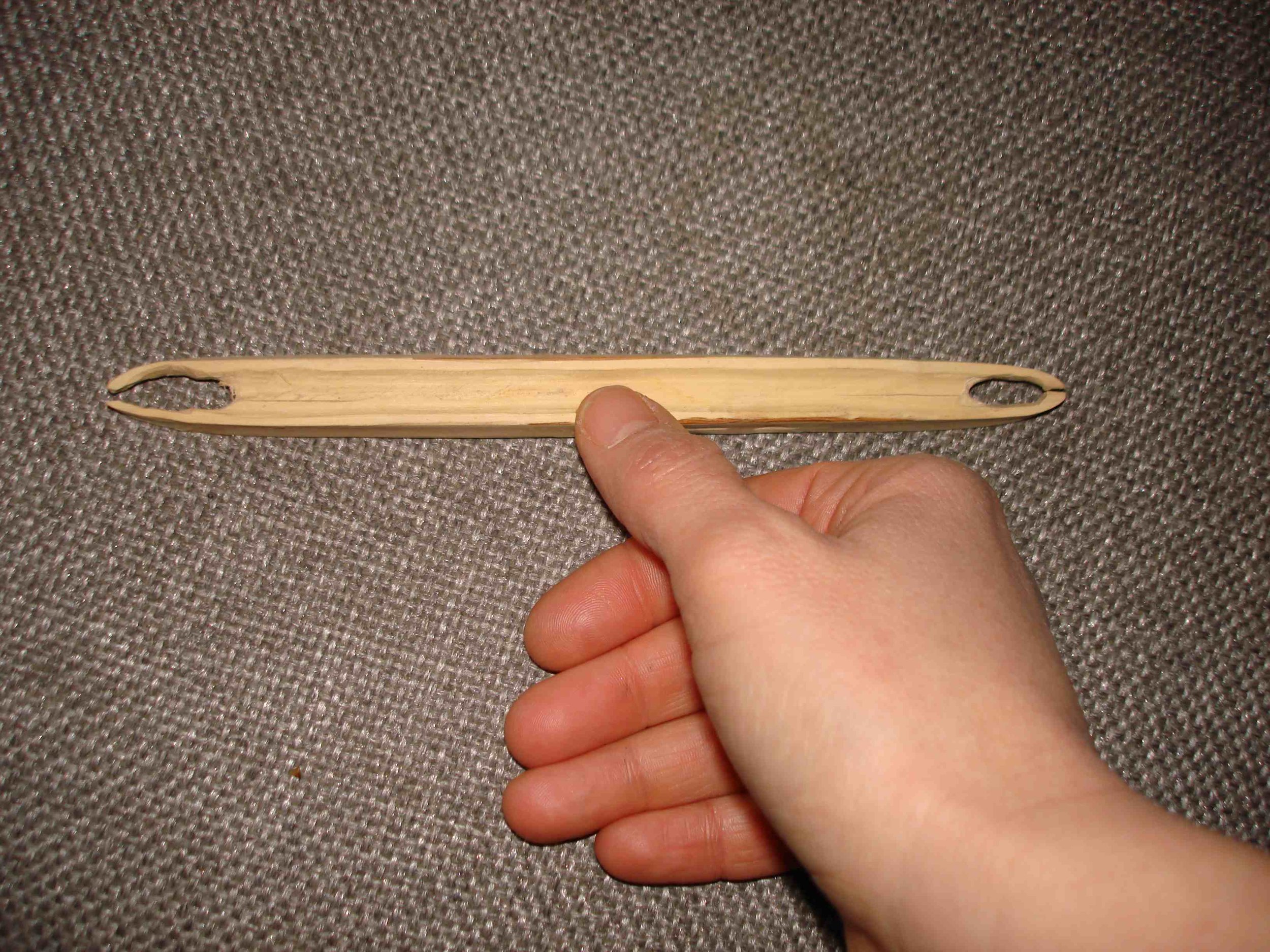

As well as having edible berries and green shoots, salmonberry is also used medicinally in some First Nations communities. Salmonberry bark, shredded and boiled, can be used as a poultice for cuts and wounds, and a solution of the boiled stems can be used as a compress on a wound. The stems were also made into a tea to treat diarrhoea. Some people also use the wood for carving small items such as shuttles for making nets, or spears for a throwing game.

Salmonberry is common in the wet areas of Wildwood, often growing under and beside red alder, which also likes damp, rich ground. If you are lucky enough to be at Wildwood when the berries are ripe, you are welcome to taste some. And, don’t forget to listen for the song of the Swainson’s Thrush!

References:

Klinkenberg, Brian. (Editor) 2017. E-Flora BC: Electronic Atlas of the Plants of British Columbia [eflora.bc.ca]. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Turner, Nancy J. (2010). Food Plants of Coastal First Peoples. Victoria: Royal BC Museum.

Turner, Nancy J. and Richard Hebda. (2012). Saanich Ethnobotany: Culturally Important Plants of the WSÁNEC’ People.Royal B.C. Museum, Victoria.

Photos courtesy of Nancy Turner

The Salmonberry flower

Lush edible berries

Salmonberry sprouts

Salmonberry net shuttle